SAT solving - An alternative to brute force bitcoin mining

Introduction

A Bitcoin mining program essentially performs the following (in pseudo-code):

while(nonce < MAX):

if sha(sha(block+nonce)) < target:

return nonce

nonce += 1

The task is to find a nonce which, as part of the bitcoin block header, hashes below a certain value.

This is a brute force approach to something-like-a preimage attack on SHA-256. The process of mining consists of finding an input to a cryptographic hash function which hashes below or equal to a fixed target value. It is brute force because at every iteration the content to be hashed is slightly changed in the hope to find a valid hash; there's no smart choice in the nonce. The choice is essentially random as this is the best you can do on such hash functions.

In this article I propose an alternative mining algorithm which does not perform a brute force search but instead attacks this problem using a number of tools used in the program verification domain to find bugs or prove properties of programs, see as example [9]. Namely, a model checker backed by a SAT solver are used to find the correct nonce or prove the absence of a valid nonce. In contrast to brute force, which actually executes and computes many hashes, my approach is only symbolically executing the hash function with added constraints which are inherent in the bitcoin mining process.

The main results besides the recipe for building a SAT-based miner, are:

- Simple parameter tuning of the used tools leads to over 1000% performance improvement.

- The proposed algorithm potentially gets more efficient with increasing bitcoin difficulty.

This is not the first time SAT solvers are used to analyse a cryptographic hash. Mate Soos et al have done interesting research on extending SAT solvers for cryptographic problems [1]; Iilya Mironov and Lintao Zhang generated hash collisions using off-the-shelf SAT solvers [2]; and many others, e.g. [3, 4]. However, to the best of my knowledge, this is the first description of an application of SAT solving to bitcoin mining.

I do not claim that it is a faster approach than brute force, however it is at least theoretically more appealing.

To aid understanding, I will introduce some basic ideas behind SAT solving and model checking. Please see the references for a better introduction to SAT solving [11] and bounded model checking [12].

SAT Solving and Model Checking

Boolean Satisfiability (SAT) is the problem of finding an assignment to a boolean formula such that the whole formula evaluates to true. As easy as it may sound, it is one of the hard, outstanding problems in computer science to efficiently answer this decision problem. There is a large and thriving community around building algorithms which solve this problem for hard formulas. Actually, each year there is a competition held where the latest, improved algorithms compete against each other on common problems. Thanks to a large number of competitors, a standard input format (DIMACS), and the easy way of benchmarking the performance of SAT solvers there have been massive improvements over the last 10 years. Today, SAT solvers are applied to many problem domains which were unthinkable a few years ago (for example they are used in commercial tools [5, 7] to verify hardware designs).

At the core of SAT solvers is a backtracking algorithm with the long name Davis–Putnam–Logemann–Loveland algorithm (DPLL) which describes a general way of finding a solution to a propositional formula in CNF format. Wikipedia summarises the algorithm well:

The basic backtracking algorithm runs by choosing a literal, assigning a truth value to it, simplifying the formula and then recursively checking if the simplified formula is satisfiable; if this is the case, the original formula is satisfiable; otherwise, the same recursive check is done assuming the opposite truth value.

A CNF formula, which is the input to a SAT solver, is made up of literals and clauses. A literal is simply a variable or its negation. A clause is a disjunction of literals. CNF is then any formula which purely consists of conjunctions of clauses.

DPLL then consists of a depth-first search of all possible variable assignments by picking an unassigned variable, inferring values of further variables which logically must follow from the current assignment, and resolving potential conflicts in the variable assignments by backtracking.

For example, given the formula $$(\lnot a \lor b) \land (\lnot a \lor c) \land (\lnot b \lor \lnot c \lor d)$$

And a partial solution so far consists of a=true then from the first two clauses we find that b=true and c=true because each clause has to be true; this implies that the last clauses has d=true as well, which yields a satisfiable solution of all variables being true.

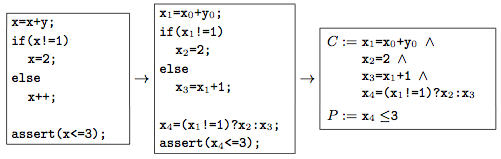

A common application of SAT solving is (bounded) model checking [12], which involves checking whether a system preserves or violates a given property, such as mutual exclusive access to a specific state in the system. Model checkers such as CBMC [5] directly translate programming languages like C into CNF formulas, in such a way that the semantics of each language construct (such as pointers arithmetic, memory model, etc) are preserved. Clearly, this is quite involved and is done in a number of steps: variables are seen as bitvectors, function calls are expanded, loops are unrolled up to a given depth, the program is transformed into static single assignment form [6], etc.

A simple example of the transformation is visible in the following figure from paper [6]:

As visible in the figure, the property which should be checked for violations is expressed as an assertion. The bitvector formula C and P above are additionally encoded as $$C \land \lnot P$$ which is then checked by a SAT solver (after converting it to CNF using the Tseitin transformation). If the formula is satisfiable then there is a variable assignment in the original program which violates the property P (because of the `not`). If it is not possible to make the formula true then the property is guaranteed to hold.

Most importantly, in case of satisfiability, the model checker can reconstruct the variable assignment and execution trace (called counterexample) which leads to the violation using the truth variable assignments provided by the solver.

Bitcoin mining using SAT Solving and Model Checking

Using the above tools we can attack the bitcoin mining problem very differently to brute force. We take an existing C implementation of sha256 from a mining program and strip away everything but the actual hash function and the basic mining procedure of sha(sha(block)). This C file is going to be the input to CBMC. The aim of this is that with the right assumptions and assertions added to the implementation, we direct the SAT solver to find a nonce. Instead of a loop which executes the hash many times and a procedure which checks if we computed a correct hash, we add constraints that when satisfied implicitly have the correct nonce in its solution.

The assumptions and assertions can be broken down to the following ideas:

- The nonce is modelled as a non-deterministic value

- The known structure of a valid hash, i.e. leading zeros, is encoded as assumptions in the model checker

- An assertion is added stating that a valid nonce does not exist

Let's explain these ideas in more detail.

The nonce

Instead of a loop that continuously increases the nonce, we declare the nonce as a non-deterministic value. This is a way of abstracting the model. In model checking, non-determinism is used to model external user input or library functions (e.g. a library function returns any possible value); in our case it is a way of moving the search from outside of the actual computation (a brute force loop) to be part of the SAT solver search. The nonce can be seen as the only "free variable" in the model.

Encoding the structure

Bitcoin mining programs always have to have a function which checks whether the computed hash is below the target (see here for an example). We could do the same and just translate this function straight to CNF, however there is a much better and more declarative solution than that in our case. Instead, we can just assume values which we know are fixed in the output of the hash. This will restrict the search space to discard any execution paths where the assumptions would not be true anymore. Because we are not in a brute force setting, but a constraint solving setting this is very simple to express. We assume the following: Only compute hashes which have N bytes [N depends on the target] of leading zeros.

In CBMC this is simple to achieve and looks about as follows:

__CPROVER_assume(

(state[7] & 0xff) == 0x00 &&

(state[7]>>8) & 0xff) == 0x00 && ... );

where state is the array containing the resulting hash. It might seem unintuitive to "fix" output variables to certain values, however remember that the code is not executed in a regular fashion but translated as a big formula of constraints. Assumptions on the outputs will result in restrictions of the input -- in our case this means only valid nonces will be considered.

This serves three purposes: it encodes the specification of a valid hash, it drives the symbolic execution only along paths which we are actually interested in, and most importantly it cuts down the CNF formula. In this case, the assumptions remove about 100'000 (out of 900k) clauses from the DIMACS file.

Again, in comparison, brute force just blindly computes hashes with no way of specifying what we are looking for. The SAT-based solution only computes hashes that comply with the mining specification of a valid hash.

The Assertion

The most important part is defining the assertion, or the property P as it is called in the section above. The key idea here is that the counterexample produced by the model checker will contain a valid nonce given a clever enough assertion.

Why is that? A bounded model checker is primarily a bug finding tool. You specify the invariant of your system, which should always hold, and the model checker will try to find an execution where this invariant is violated (i.e. where there was a satisfiable solution). That is why the P above is negated in the formula.

Thus, the invariant, our P, is set to "No valid nonce exists". This is naturally expressed as the assertion

assert(hash > target);

Which the model checker will encode to its negation as "a valid nonce does exist", i.e. the negation of the above assertion. If a satisfiable solution is found, we will get an execution path to a valid nonce value.

In reality, this is encoded more elegantly. Since the leading zeros of a hash are already assumed to be true, all that remains to be asserted is that the value of the first non-zero byte in the valid hash will be below the target at that position. Again, we know the position of the non-zero byte for certain because of the target. For example, if our current target is the following:

00 00 00 00 00 00 04FA 620000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

^ ^

state[7] state[6]

Then the following assertion states that a certain byte in state[6] of the hash has to be above 0x04.

if(((state[6] >> 8) & 0xff) > 0x04) {

flag = 1;

}

assert(flag == 1);

As the assertion is negated, the SAT solver will be instructed to find a way to make the flag equal to 0. The only way this can be done is by playing with the only free variable in the model -- the nonce. In that way, we just translated the bitcoin mining problem into SAT solving land.

Producing a Counterexample

Combining the ideas from the above sections results in a conceptual SAT-based bitcoin mining framework. In pseudo C code this looks as follows:

void satcoin(unsigned int *block) {

// offset into the block header

unsigned int *nonce = block+N;

// non-deterministically assign a value to the nonce

*nonce = nondet_int();

// 'sha' is a standard SHA-256 implementation

hash = sha(sha(block));

// assume leading zeros

assume(hash[0] == 0x00 && ...);

// encode a state where byte M of hash is bigger than target

int flag = 0;

if(hash[M] > target[M])

flag = 1;

// assert there's no hash that is below target

assert(flag == 1);

}

This program is the input to CBMC, which will encode it to CNF and pass it on to a built-in SAT solver, or alternatively output it as DIMACS to use a different solver. The advantage of using the built-in solver is that, in case of satisfiability, the model checker can easily retrieve a counterexample from the solution which consists of all variable assignments in the solution.

A violation of the assertion implies a hash below the target is found. Let us inspect a counterexample when run on the genesis block as input. At state 4730 below, the flag was found to be 0 which violates the assertion. Moving upwards in the execution trace we find a valid hash in state 4719. Finally, the value of the non-deterministically chosen nonce is recovered in state 1604.

State 1604 file satcoin.c line 108 function verifyhash

----------------------------------------------------

c::verifyhash::$tmp::return_value_nondet_uint$1=497822588

(00011101101011000010101101111100)

[.....]

State 4719 file satcoin.c line 77 function sha_processchunk

----------------------------------------------------

verifyhash::1::state={ 1877117962, 3069293426, 3248923206,

2925786959, 2468250469, 3780774044, 1758861568, 0 }

[.....]

State 4730 file satcoin.c line 153 function verifyhash

----------------------------------------------------

verifyhash::1::flag=0 (00000000000000000000000000000000)

Violated property:

file satcoin.c line 160 function verifyhash

assertion

flag == 1

VERIFICATION FAILED

Two lines of python verify that the hash is correct (when compared with the genesis block):

>>> ints = [1877117962, 3069293426, 3248923206, 2925786959, 2468250469, 3780774044, 1758861568, 0]

>>> struct.pack('>8I', *ints).encode('hex_codec')

'6fe28c0ab6f1b372c1a6a246ae63f74f931e8365e15a089c68d6190000000000'

Evaluation

The implementation of the above program generates a large CNF formula with about 250'000 variables and 850'000 clauses. In order to evaluate its performance I generated two benchmark files where one has a satisfiable solution and the other does not. I restricted the nonce range (the possible values to be chosen) to 1000 values for each file. The files are available on the following github project.

Current state of the art SAT solvers, most having won one or multiple competitions, are tested on the files out_1k_sat.cnf and out_1k_unsat.cnf. Unsurprisingly, the solvers are not capable of solving this problem efficiently as of now. However, it is interesting to see the differences in runtime.

First the table for out_1k_unsat.cnf.

| SAT Solver | Time to UNSAT |

|---|---|

| Cryptominisat 2.9.2 | 49s |

| Cbmc 4.0 Minisat | 1m18s |

| Rsat 2.01 | 2m08s |

| restartsat | 1m35s |

| Minisat 2.0 | 2m09s | ManySat 2.0 | 2m24s |

| Precosat 576 | 2m30s |

| Glucose 2.1 | 2m35s |

| ZChaff 2004.11.15 | 4m10s |

| Lingeling ala | Did not terminate (40m+) |

Cryptominisat wins the UNSAT challenge by being faster than all the other solvers. This is interesting as Cryptominisat has been specifically tuned towards cryptographic problems as it is able to detect and treat xor clauses differently to normal clauses [1]. This feature is extensively used in this case, in the above run the solver found over 95000 non-binary xor clauses.

In UNSAT, every solver has to perform the same amount of basic work of trying out 1000 nonce values. The crypto-focused optimisations of Cryptominisat could potentially have helped in solving this more efficiently than the other solvers.

Next, the results for out_1k_sat.cnf.

| SAT Solver | Time to SAT |

|---|---|

| Cryptominisat 2.9.2 | 42s |

| Cbmc 4.0 Minisat | 1m05s |

| Rsat 2.01 | 1m29s |

| restartsat | 38s |

| Minisat 2.0 | 1m70s | ManySat 2.0 | 1m16s |

| Precosat 576 | 1m23s |

| Glucose 2.1 | 45s |

| ZChaff 2004.11.15 | 22s |

| Lingeling ala | Did not terminate |

First, it is unsurprising that the SAT timings are generally lower than UNSAT as the solvers do not have to try all possible nonce values. However, it is very surprising that ZChaff wins the SAT challenge with a good margin to the next solver. ZChaff is the oldest of all solvers presented here, the version I am using is 9 years old. This could indicate that the heuristics applied by modern SAT solvers do not help in this particular instance.

Generally, it is not known what makes a SAT instance hard or easy, which leaves only speculation or analysis of the stats provided by the SAT solvers to come to useful conclusions. I could speculate that the avalanche effect of the hash function produces a very structured CNF formula with high dependencies between clauses and variables. Perhaps a higher degree of randomisation applied by heuristics performs less well than straight-forward DPLL. I leave this to someone with more SAT solving knowledge to decide.

Let's try to improve these numbers a bit with some parameter tuning.

Tuning and Improvements

While the performance numbers are not great (compared to GPU mining) we have to keep in mind that this is entirely unoptimised and there are many ways of how this can be sped up. To give an idea of the performance gains that can be achieved with little effort I am going to use a combination of features:

- Firstly, the model checker allows slicing the algorithm at the program level (before translating it to CNF). Here, anything that is unrelated to the assertion will be sliced away. As the code for the miner is relatively small and none of the SHA-256 code paths are unused, this only slims down the CNF formula by 500 clauses, however it still does have an effect at times.

- Secondly, SAT solvers usually have a large number of parameters to play with like the frequency to pick a random branching choice as decision heuristic.

In this experiment, I am going to use Cryptominisat as it performed well in the UNSAT challenge and has a large number of parameters with parameter tuning and slicing.

| File | Nonce Range | Timing | Speedup | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| out_1k_sat.cnf | 1000 | 8s | 525% | noconglomerate, restrict=32 |

| out_1k_sat.cnf | 1000 | 4s | 1050% | plain, restrict=32 |

| out_10k_sat_sliced.cnf | 10'000 | 36s | 600% (original 3m39s) | noconglomerate, restrict=4500 |

Simply adding two parameters to Cryptominisat already improves the performance by over 500%. The restrict parameter is a way to only branch on the 32 most active variables which is intended for cryptography key search -- 32 was picked arbitrarily. In the second row, I tried running it with the plain parameter which deactivates all simplification heuristics, in order to see if the speculations around the ZChaff-speed improvement could also apply to Cryptominisat. Indeed, a 1000% improvement clearly shows that a simpler solver performs better on this instance.

For the last row, I increased the nonce range to 10'000 values which leads to an interesting result. The unoptimised run of this file is only 3m39s; this is half the expected time when we take the 42s benchmark on 1000 nonces and assume that the search time increases linearly with the nonce range. This does not seem to be the case. Apart from that observation, a 600% improvement is achieved with naive parameter tuning.

Apart from parameter tuning there's quite a few things that should have an even larger impact on performance. Here are a couple of examples:

- It is not using the midstate. This should be the most obvious way of improving performance. With the midstate precomputed, it will make one less hash call, which dramatically reduces the size of the formula (remember there are no function calls but everything is inlined).

- As demonstrated, tailored SAT solvers perform better than more off-the-shelf ones. Tuning the SAT solver combined with encoding the problem better (see next point) is definitely the way to get better performance. Most solvers have a large number of parameters to tweak. Additionally, parallel, GPU and FPGA based solvers do exist [8].

- Encoding the problem to CNF can be done much more efficiently and directly than what can be achieved with a general purpose model checker such as CBMC. For example, the authors of this paper [10] developed their own toolkit to translate hash functions to CNF.

- Perhaps most interestingly, additional constraints and assumptions could be found which would potentially speed up the search even further.

Bitcoin Difficulty and Assumptions

A very intriguing, and perhaps unintuitive property of the algorithm proposed is that with increasing bitcoin difficulty, or equally lower target, the search could become more efficient, at least in theory. This is because we can assume more about the structure of a valid hash -- a lower target means more leading zeros which are assumed to be zero in the SAT-based algorithm.

If this is true and is a substantial effect then this is an important issue since the rate of the money supply is regulated with the difficulty. The higher the difficulty, the less likely it is that an individual block has a valid nonce. However, conventional mining algorithms always have to perform the same amount of work (i.e. try 4 billion nonce values) to reject a block. On the other hand, "Satcoin" miners will get progressively faster which could lead to imbalances in the controlled supply. These are all just speculations and depend on many factors, first and foremost how well the SAT-based approach can be improved and whether the probability of finding a valid nonce does not dwarf the efficiency gain of the algorithm.

To explore this hypothesis, I also ran the algorithm on block 218430 that was found at the end of January 2013. Since it is obviously a block later in the history than the genesis block (block 0) its target is smaller. The target of the genesis block is the following:

00000000ffff0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

The one of block 218430 is clearly lower and shows more leading zeros which means more of the hash output will be 'fixed' (assumed to be zero) in advance:

00000000000005a6b10000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

The next table again shows the runtimes to SAT for 1000 nonces on block 218430. The last column shows the speedup against block 0.

| SAT Solver | Time to SAT | Speedup |

|---|---|---|

| Cryptominisat 2.9.2 | 54s | -10% |

| Cbmc 4.0 Minisat | 1m11s | -9% |

| Rsat 2.01 | 1m10s | +27% |

| restartsat | 26s | +42% |

| Minisat 2.0 | Did not terminate | ManySat 2.0 | 39s | +94% |

| Precosat 576 | 25s | +232% |

| Glucose 2.1 | 1m17s | -42% |

| ZChaff 2004.11.15 | Did not terminate | |

| Lingeling ala | Did not terminate |

Initially, two more solvers, Minisat and ZChaff, did not terminate within the specified timeout (40 minutes). Apart from that, we see a number of good speed ups compared to the Block 0 timings. Generally, it is hard to benchmark SAT solvers (see [13]) since comparing different heuristics of different solvers can lead to inconsistent results. The paper [13] on benchmarking SAT solver suggests dropping all timeouts and using the geometric mean (in a slightly different context) to evaluate runtimes and speedups. The geometric mean runtime for block 0 over all solvers is 59s, while block 218430 clocks in at 47s, which is indeed faster.

Lastly, let us apply the ZChaff-speed up lesson from the previous section and run the same file with Cryptominisat and the parameters "plain, restrict=32". The result is 2.5s until a solution is found which is 2160% faster than without tuning and another 160% speedup to the best time of block 0 in the previous section. Looking at the solver statistics shows less restarts (5 instead of 6), less conflicts (858 vs 158), and less conflict literals (4785 vs 12686) compared to block 0 which could indeed hint towards higher algorithmic efficiency with growing bitcoin difficulty.

Conclusion

I introduced a novel algorithm to solve the bitcoin mining problem without using (explicit) brute force. Instead, the nonce search is encoded as a decision problem and solved by a SAT solver in such a way that a satisfiable instance contains a valid nonce. The key ingredients in the algorithm are a non-deterministic nonce and the ability to take advantage of the known structure of a valid hash using assume statements.

A couple of benchmarks demonstrated that already with simple parameter tuning dramatic speed ups can be achieved. Additionally, I explored the contentious claim that the algorithm might get more efficient with increasing bitcoin difficulty. Initial tests showed that block 218430 with considerably higher difficulty is solved more efficiently than the genesis block 0 for a given nonce range.

References

[1] Mate Soos, Karsten Nohl, and Claude Castelluccia: Extending SAT Solvers to Cryptographic Problems. SAT 2009. pdf

[2] Ilya Mironov and Lintao Zhang: Applications of SAT Solvers to Cryptanalysis of Hash Functions. SAT 2006. pdf

[3] Fabio Massacci: Using Walk-SAT and Rel-SAT for cryptographic key search. IJCAI 1999. pdf

[4] Benjamin Bloom: SAT Solver Attacks on CubeHash. Thesis 2010. pdf

[5] http://www.cprover.org/cbmc/

[6] Edmund Clarke, Daniel Kroening, and Flavio Lerda: A tool for checking ANSI-C programs. TACAS 2004. pdf

[7] Ben Chelf and Andy Chou: The next generation of static analysis. White paper. pdf

[8] Leopold Haller and Satnam Singh: Relieving Capacity Limits on FPGA-Based SAT-Solvers. pdf

[9] Jonathan Heusser and Pasquale Malacaria: Quantifying information leaks in software. ACSAC 2010. acm pdf

[10] Pawel Morawiecki and Marian Srebrny: A SAT-based preimage analysis of reduced KECCAK hash functions. 2010. pdf

[11] Koen Claessen, Niklas Een, Mary Sheeran, and Niklas Sorensson: SAT-solving in practice. 2012. pdf

[12] Edmund Clarke, Armin Biere, Richard Raimi, and Yunshan Zhu: Bounded Model Checking Using Satisfiability Solving. Form. Methods Syst. Des. 2001. pdf

[13] Emmanuel Zarpas: Benchmarking SAT Solvers for Bounded Model Checking. SAT 2005. pdf

comments powered by Disqus